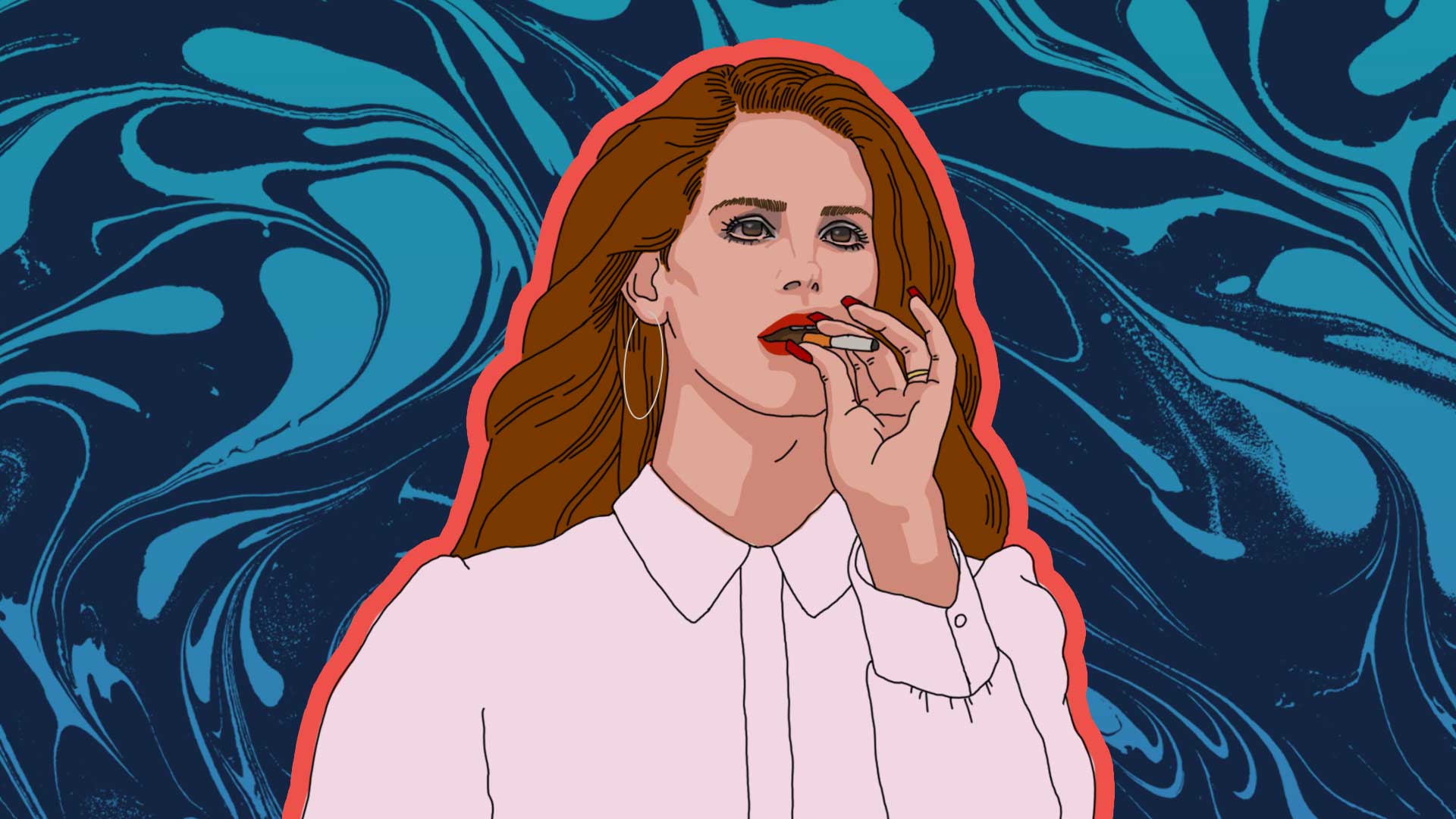

It is nearly impossible to imagine the contemporary pop music scene without the influence of one particular artist with a penchant for writing about older boyfriends, money, and rural America. Widely credited for popularizing the now ubiquitous Sad Girl sound of modern popular songwriting, Elizabeth Woolridge Grant – better known by stage name Lana Del Rey – has become synonymous with the music, aesthetic, and pop culture of the 2010s.

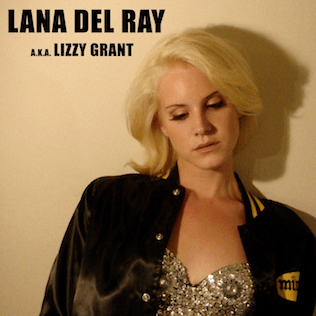

Lizzy Grant

Before she was Lana, Grant released music under the name Lizzy Grant. Her eponymous album – known affectionately to fans as AKA Lizzy Grant – was released digitally in 2010. It was quickly scrapped from the market, Grant citing legal issues with her label, buying back the rights, and promising an eventual physical release of the album. To this day, however, AKA remains unreleased. If curious listeners hope for a chance to hear it, their options are to scour the recesses of Soundcloud or to wait for some more tech-savvy fans to upload a version onto Spotify or YouTube under a pseudonym. Typically, these get flagged and taken down within weeks.

Seeing as there’s constant monitoring of AKA’s content more than a decade after its brief, initial release, fans constantly speculate Grant will release it as an official album. The more time passes, though, the less likely this seems to ever become a reality. Grant has progressed and evolved so much as a musician – and person – since those early days as Lizzy that, to revisit that particular era, now, would feel jarring and out-of-step with the woman she’s matured into.

Written by Grant and produced by David Kahne, the album possesses an almost caricaturesque aura about it. With songs like Queen of the Gas Station or Raise Me Up (Mississippi South), it’s obvious Grant was not inspired by her East Coast boarding school upbringing when writing. Peppered with references to trailer parks, vague southern twang, and sung almost entirely in an artificially high register, AKA is an ode to the character of Lizzy. The stripped-down, psychedelic rock quality whispers promises of what was to come musically for Grant, while certain lyrical themes, namely her captivating way of writing about love, are some Grant continues to explore.

In hindsight, the album feels borderline comedic today with its insistence on portraying a wide-eyed, trailer-trash, naive little girl character. Its unreleased status allows it an air of mystery, amplified by a low sound quality. AKA is a romantic look into what a young woman believed a pop album should be in order to succeed.

Born to Die, Paradise, and Ultraviolence

Instead of physically releasing AKA as promised, in 2012 Grant switched labels and released the now era-defining Born to Die under Interscope records. This album exploded onto the charts, bringing Grant into the harsh spotlight of ruthless early 2010s music journalism. From Pitchfork to Rolling Stone, there was no shortage of opinions. “She’s just another aspiring singer who wasn’t ready to make an album yet. Given her chic image, it’s a surprise how dull, dreary and pop-starved Born to Die is,” Rob Sheffield of Rolling Stone wrote. Pitchfork rated the album a 5.5 out of 10 (it was later rescored to a 7.8 in October 2021). People claimed she was an industry plant. How exactly did a virtually unknown singer suddenly feature at the top of the charts singing about wanting men to use her for money? Critics thought the album overproduced, bloated, and lyrically distasteful. Grant was criticized for supposedly glorifying abusive relationships. If AKA had been a caricature of a person, Born to Die was its natural progression into an escapist, fantasy world.

Seemingly undeterred by the criticism, ten months later she released The Paradise Edition of the album which features an additional newly recorded eight tracks. Just as cinematic as its original edition, both album and EP teeter on the edge of ridiculous as they navigate themes of femininity, love, and lust in a manner so corny and cliché that it can’t help but feel honest. It’s hard to say whether critics were motivated by aversion toward such unsightly topics in an era of what was supposed to be Girl-Power pop (Beyoncé had just released Run the World (Girls) the year before), or whether the ironic detachment of the time had no way to process such a playfully unsophisticated work – either way, Grant was polarizing.

Following the popularity of Born to Die, in 2014 Grant released her second studio album, Ultraviolence, produced by Dan Auerbach of The Black Keys. Equally as cinematic, Ultraviolence shamelessly doubles down on exploring femininity, relationships, and wealth in Grant’s particular, cheeky way. Grant’s second album, however, is darker than its predecessor. Perhaps impacted by Grant’s real-life tragedy, there’s an inescapable presence of death and loneliness in the lyricism, and the production – while still theatrical – is more turned inward. Brimming with unforgettable lines like “he hit me and it felt like a kiss”, teenage girls worldwide further indulged in the morally questionable fantasy of Lana Del Rey. She had cemented herself a symbol for young women who didn’t typically see themselves represented in the forced optimism of popular culture.

Honeymoon, Lust for Life, Norman F***ing Rockwell

Over the next few albums that Grant released, the lines between persona and real self began to blur. Though the facade still existed, it eventually began to crack and allow in some less grandiose lyricism. It was 2015, Grant turned thirty and released Honeymoon. The themes of Grant’s past works remain present, but are approached in a mournful tone rather than a celebratory one. The production is still reminiscent of a soundtrack but, rather than overpower, it recedes into the background. The album is more self-aware and mature than its predecessors. It exudes the regret and fear that accompany a woman aging out of her twenties. “I don’t matter to anyone/ But Hollywood legends / Will never grow old.”

Having secured her status as a respected musician, Grant diverged from her usual style with her 2017 release of Lust for Life. Considered by many to be her most experimental work, it blends styles from folk to trap and features both Stevie Nicks and The Weeknd. Lust for Life is Grant’s first time acknowledging her existence within our world rather than the fabricated fantasyland her previous albums seem to inhabit. “Is this the end of an era? Is this the end of America?” she asks in the album’s 11th track, When the World Was At War, We Kept Dancing.

Clearly perturbed by the uncertainty of the late 2010s political climate, and perhaps having shed the particular narcissism that often afflicts those in their twenties, Grant figured that a woman with as much sway as she should not remain silent. This resulted in a critically-acclaimed album that was a clear demarcation between the old and new Lana.

By the time of Norman F***ing Rockwell’s release in 2019, Grant had quite obviously grown out of the character she’d been embodying over the past decade. Produced by Jack Antonoff, the album is characteristic of his stripped-down sound. This, along with the intensely personal lyricism allow it to become some of Grant’s most intimate work. There are political references woven casually throughout the album – a stark contrast from her previous album where nods to current events felt shoehorned in. Despite the apparent world-building involved in the writing, NFR feels simple and direct in its delivery. It’s the product of Grant’s masterful sprinkling of the fantastical into the personal.

Chemtrails Over the Country Club, Blue Banisters, Did you know that there’s a tunnel under Ocean Blvd

In the last two years, Grant has released three studio albums, all co-produced by Antonoff. Chemtrails Over the Country Club and Blue Banisters, released in 2021 and 2022 respectively, are soft and folksy. They seem to exist in a different universe than Born to Die. There’s a maturation that’s noticeable in Grant’s songwriting. The persona she once relied on is hardly present in the lyrics. She isn’t playing a character anymore. Gone are cartoonish references to older men, money, or drugs. More reminiscent of a personal diary than a pop album, Grant writes of loss, of being a woman past her prime, and of the loneliness that accompanies it. While the albums were not commercial successes, they were a clear indication that mainstream approval is no longer something Grant pays any mind to.

In March of 2023, Grant released her ninth studio album, Did you know that there’s a tunnel under Ocean Blvd. Featuring rambling intimate lyrics, trap beats, a Stevie Nicks feature, and hommages to her loved ones, Ocean Blvd seems to sum up her entire discography to-date. It’s by no means a cohesive pop album but that is not what Grant seeks to create anymore. “With this album, the majority of it is my innermost thoughts,” she told Billie Eilish for Interview Magazine.

Over the last decade, fans and critics alike have watched Grant grow from woman-child to woman. Aging out of her perfectly curated persona, she chose to embrace this rather than let it deter her. Having the protective shield of youth forced away from her, it would have been so easy for her to recede into obscurity. Instead, she opts to infuse more of herself into her songwriting than ever before. “Your life is your art,” she says. How lucky we are that she’s realized that.

Written by Ari Mazur

Illustration by Yihong Guo