As the live sound engineer and co-founder of Montreal venue The Diving Bell Social Club (and an RAC alumnus!) Evan Johnston has set up and recorded live performances in every musical genre, whether it’s for rock bands or orchestras. His work is guided by simple tenets that wholly apply to both live performances and recordings: understand the specific sonic needs of the musicians and each of their instruments, master the tools and equipment necessary to perfectly calibrate a space, connect with the performers and engineers.

When the pandemic hit, Evan was immediately prepared to launch high-quality, engaging livestream shows, thanks to the equipment he had on hand and his experience built up over seven years working in sound. He sat down with RAC to reflect on the useful lessons he’s carried over into his career, the advantages of being prepared for anything, and the simple tricks to make live sound all the more magical.

RAC: What first led you to working in sound?

Evan: Ever since I was old enough to sit up straight, I’ve been playing instruments. I started with violin, then double bass, and guitar. At about 15 years old, I started playing in bands. We cut a couple albums and I always thought the process was fascinating. I started out, like many do, on a stereo cassette tape recorder, then we got a Yamaha straight-to-CD 8-channel mixer.

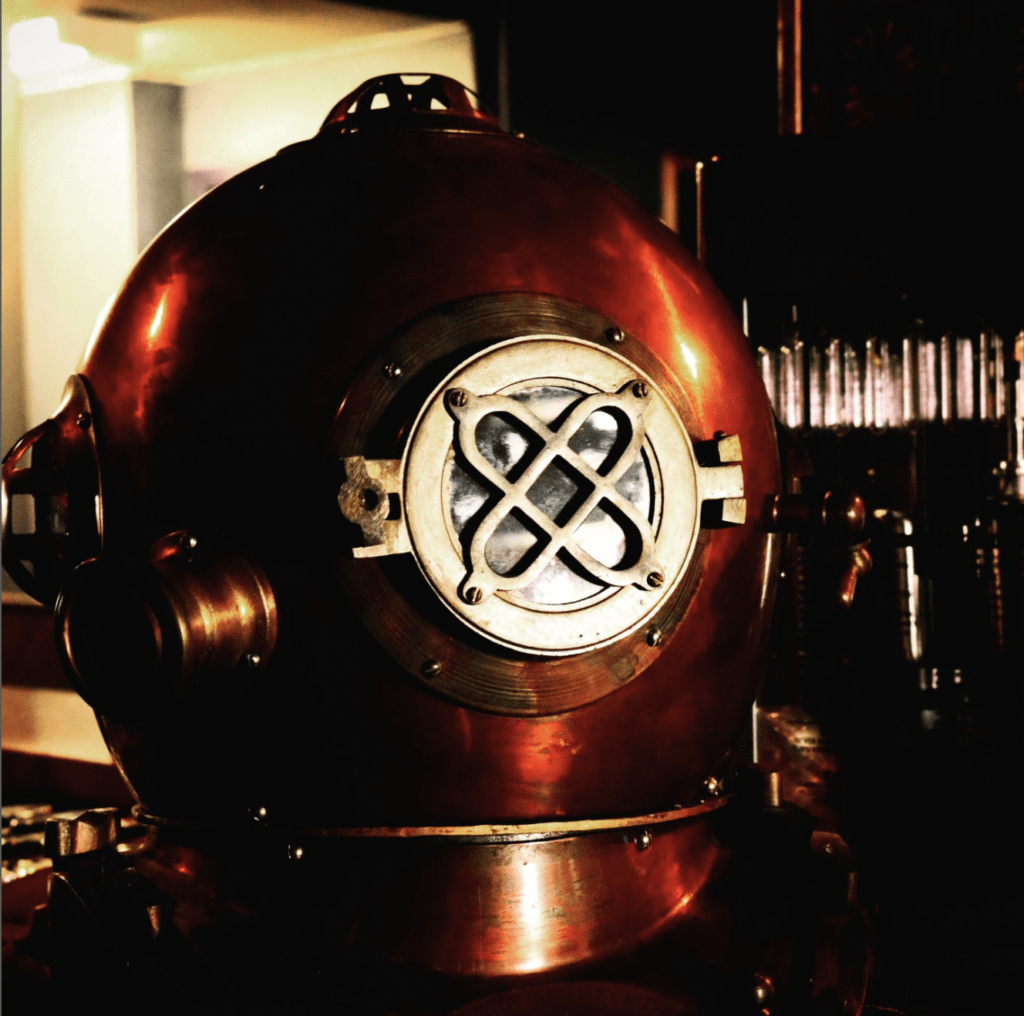

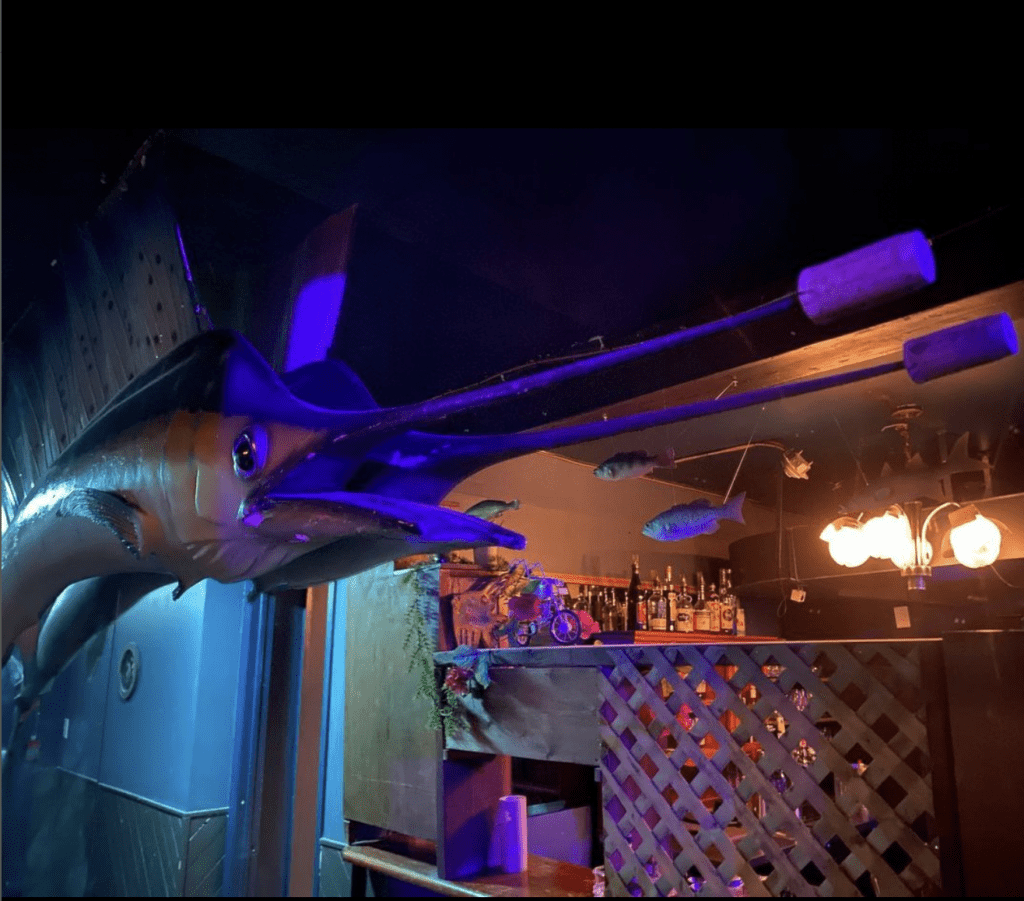

I first went to MacEwan University for jazz and blues studies in guitar, then wanted to get more into production and live sound, so I moved to Montreal from Edmonton to go to RAC! After that, I used my skills by doing random live sound gigs at bars and venues. I opened up a DIY venue with some friends called The Bog and got involved in setting up a really good sound system there. My Bog partners and I eventually felt that we were outgrowing the DIY space, so we opened up The Diving Bell Social Club.

RAC: What’s a lesson you learned studying audio that you’ve held on to?

Evan: Understanding sound as a science was really helpful. It’s like cooking or baking – you can read instructions on how to do something, but if you don’t understand the underlying fundamentals of how sound works as a pressure wave, it’s harder to fully grasp it.

A lesson I learned at RAC for dealing with live sound was that whether you’re using analog gear or going through a DAW, visually imagine the signal chain (where you want the sound to come from and where you want it to go). If you trace a single unbroken line, it will help troubleshoot when something isn’t working properly.

RAC: What’s an unexpected area you’ve found your skills can be applied to?

Evan: I didn’t expect to be as involved in video editing. Half of video editing is the sound. I’d argue that when you’re making a video, the sound quality is more important than the video at times. If you’re watching a great video with bad sound, you’ll notice.

RAC: What was some of the first equipment you invested in when opening The Diving Bell Social Club?

Evan: We made the decision that, despite not having a lot of capital to start the venue, the majority of our investment would go into sound equipment. We knew we wanted to create a space with incredible sound. So, we got a Behringer X32 digital mixing console, a set of QFS KW153 speakers with subwoofers, as well as a digital snake. When we were running The Bog, it was all analog. We were constantly dealing with buzzing and a myriad of issues, so it was really important we start off on the right foot.

RAC: Was it a significant upgrade going from analog to digital?

Evan: Huge. If you’re doing a soundcheck on an analog board for three bands a night, aside from taking a picture of where all of your rotary faders are, they won’t play in the same state. On the digital mixing board, we save our soundchecks, and then throughout the night we load the scene and it’s exactly how we want it to sound.

RAC: What are some essential pieces that even the most basic sound system should include?

Evan: Whether you’re going digital or analog, you’re going to need a multiband EQ, a compressor, and ideally some simple reverb. I think you could do it with that alone, but if you have the means to get a digital board, it’s night and day.

RAC: What’s your favourite type of show to do sound for? What’s the hardest?

Evan: I think my favourite type of show is orchestral. Everything is so subtle with your mic placement, your panning, and your EQ in particular. You’re really just trying to enhance the sound and mix it properly without adding too much flavour. When you’re successful, it’s very satisfying.

I think that very large and loud bands are the hardest to do sound for. When you have a really loud guitar, it’s a struggle to assure the guitar player that they can turn down their amp and it will sound great out in the room. Oftentimes, guitarists will turn up their amps and you’re kind of raising the noise floor at all times.

RAC: How do you establish clear communication and a solid relationship when working with artists?

Evan: I think it’s incredibly important for anyone doing live sound to get out of the booth at the beginning, introduce yourself and be on a first-name basis with everyone you’re doing sound for. If they have respect for what you’re doing and know that you respect what they’re doing, everything’s going to go smoother.

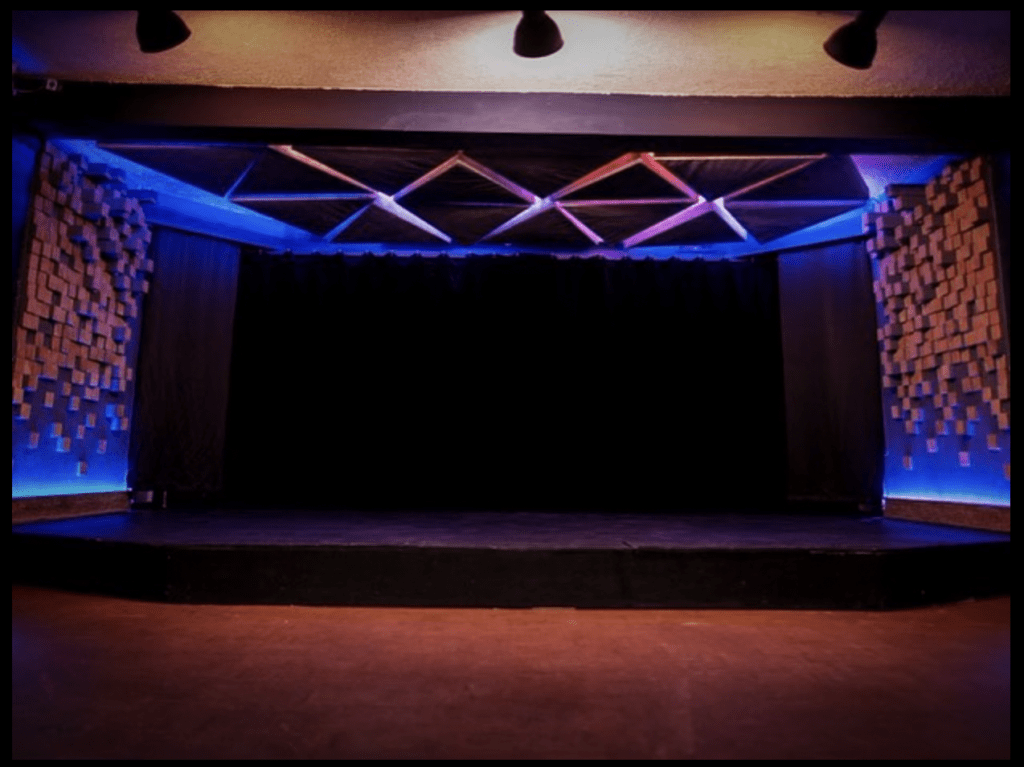

RAC: How did you figure out the best way to calibrate the space’s sound system?

Evan: A big part of it was treating our room as well as we could – we built extra walls with resilient channels for soundproofing, added some bass traps and diffusers for high frequencies, and put high-density foam on the windows so there wasn’t a flat surface behind the stage.

RAC: Can you recommend any mixing consoles or microphones for live vocals?

Evan: The Behringer X32 mixing console. It’s a staple for a lot of live music venues. Then, for live vocals, the classic Shure SM58 dynamic microphone.

RAC: When the pandemic hit, The Diving Bell was early to jump on offering livestream shows. How did you prepare for those?

Evan: We had never done anything like it before. In the end, the trick came down to mixing live sound and then sending it out to the stream, so that it synced with the video. Without a stream, you’re mixing for the room. When you’re streaming though, you’re mixing for headphones or an iPhone speaker. Our solution was to have bands play with the house speakers turned off, with monitors alone. I was at the board, mixing from my headphones, and periodically checking between what the board was sending out and what my audio interface was receiving and then sending out to the stream. We had to address some latency issues, but overall it went pretty well.

For anyone looking to do live streaming, OBS is a free open source streaming software that works great. You can use multiple cameras and audio sources all for free.

RAC: As venues reopen, are you experiencing a high demand for live events? Do you foresee this leading to more jobs?

Evan: I think so. The caveat is that the pandemic shut down a lot of venues, so while there is a big demand for shows again, the spaces in which they can be performed are limited. But there’s definitely potential for more availability for sound jobs and we’re seeing an explosion of live event requests which is nice.

RAC: Do you plan on carrying forward any lessons learned in the pandemic?

Evan: Yes! Microphone cleanliness and protocol. Before the pandemic, no one was really thinking about the fact that you’ve got multiple people sharing the mic over the course of one night. Now we have extra microphones and a procedure for cleaning between artists. The pandemic also opened the door for us to confidently say that we can stream a show to Twitch at a moment’s notice if we need to.

—Final notes—

When working in live sound, you need to stay on your toes. Evan says it’s important to be organized and to familiarize yourself with the space to avoid any potential disasters. “Always keep track of your cables,” he suggests. “Ideally, number or label your cables so that you can know in an instant where something is plugged in. You can stay on the board and ask the artist what’s plugged into their mic.” He also recommends always having a spare guitar (in case someone breaks a string), batteries for active pickups, and more mics than you think you need.

When it comes to landing that dream job at your favourite venue, Evan believes that oftentimes a strong resume isn’t enough. In his experience, venues usually hire people they already know and trust. “If you want to work somewhere, go see shows there and grab a couple drinks,” he says. “Introduce yourself to the sound person and to the owners, and make it known that it’s something you’d like to do. It goes a lot farther than a random resume.”

Written by Maryse Bernard

Illustration by Yihong Guo